In an increasingly globalised world, leadership cannot be defined by a single universal approach. Cultural context plays a critical role in shaping leadership practices, particularly in communication and decision-making. Geert Hofstede was among the first scholars to challenge the universality of American management theories, demonstrating through his cross-national research at IBM in the 1970s that leadership is deeply influenced by cultural factors. His work laid the foundation for comparative and international management studies, advocating for culturally sensitive leadership approaches (Jackson, 2020). Expanding on this, Meyer (2014) identified eight cultural dimensions—such as low-context versus high-context communication and egalitarian versus hierarchical leadership—that shape cross-cultural interactions. This article focuses on one key dimension: power distance.

Power distance refers to the extent to which inequality in power is accepted and expected in a society. In high power distance cultures, authority is consolidated in a few hands, and leaders wield control through rigid structures and formal rituals. These societies place high value on hierarchy, where respect for leaders is non-negotiable and reinforced by clear boundaries between those who hold power and their subordinates. On the other hand, low power distance cultures break down these barriers, promoting a more egalitarian environment where collaboration and equality are key. Leadership in these cultures tends to be more participatory, with authority diffused across multiple levels. Understanding power distance is essential for leaders operating in international and multicultural environments. Leaders who recognise these differences can tailor their management approaches to foster effective communication, employee engagement, and workplace harmony.

Power Distance in Europe: Historical and Cultural Influences

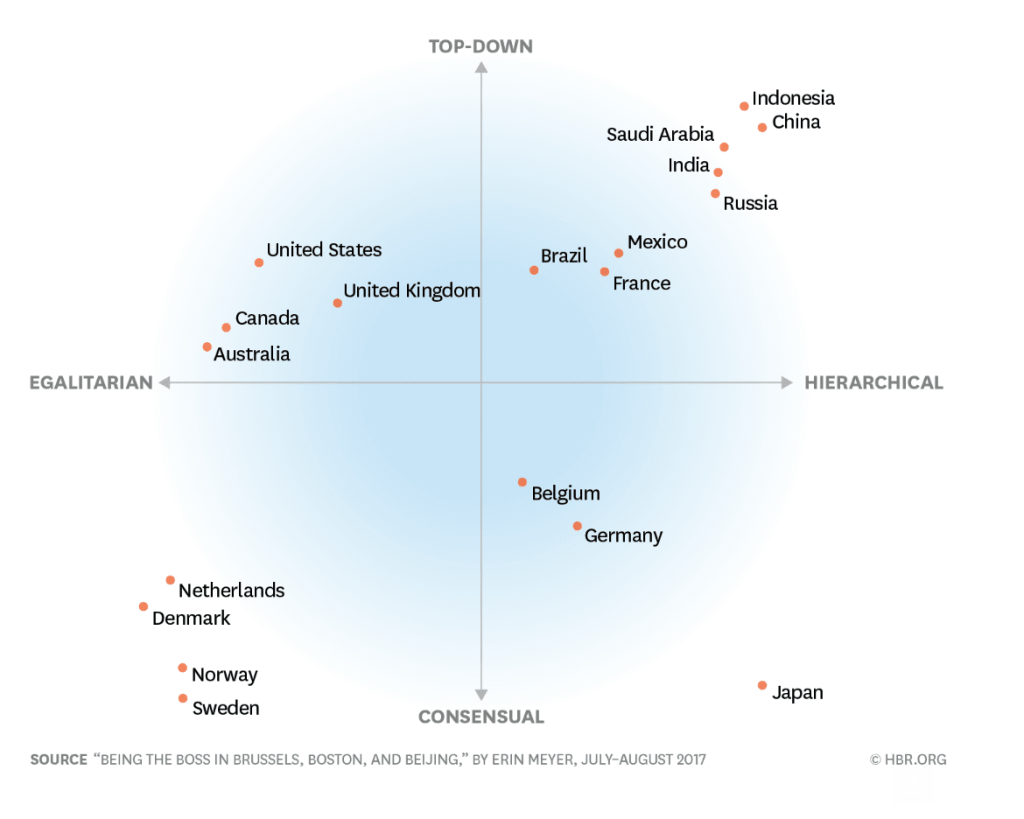

Europe presents a spectrum of power distance variations shaped by historical, political, and economic factors. Southern European countries, such as Spain, Italy, and France, have traditionally exhibited high power distance due to their monarchic and religious histories, where hierarchical structures and authoritative leadership were the norm (Brewster, Chung, & Sparrow, 2016). France, for example, has a long history of centralised authority dating back to the absolute monarchy, which still influences corporate leadership styles today. Similarly, the legacy of the Roman Empire’s top-down authority structure continues to exert a significant impact on leadership styles in Italy and Spain. Leaders are often seen as figures of power and control, using formal titles and symbols to reinforce their status, a reflection of the centralised leadership practices from centuries ago.

Conversely, Northern European countries such as Sweden, Denmark, and the Netherlands have developed low power distance cultures. The Protestant Reformation, combined with strong welfare states and democratic governance, has shaped leadership approaches that emphasise equality, participation, and employee empowerment (Hofstede, 2001). In Scandinavia, Viking societies fostered a leadership style in which authority was earned through actions and competence rather than titles. This egalitarian approach, based on shared responsibility and collective decision-making, laid the foundation for the participative cultures seen today in Denmark, Sweden, and Norway. Leadership in these countries is characterised by collaboration rather than hierarchy—leaders work alongside employees in open-plan offices, engage in informal discussions, and share meals, fostering a culture of openness and teamwork. Authority is not imposed but earned through expertise, and decision-making is a collective effort (Meyer, 2014).

Post-communist countries in Eastern Europe, such as Russia, Poland, and Hungary, historically exhibited high power distance due to centralised political structures under Soviet influence. However, globalisation and economic liberalisation have led to shifts toward more participatory leadership styles in some organisations (House et al., 2004). These changes are particularly evident in younger, multinational corporations operating within these regions, where a blend of hierarchical respect and collaborative decision-making is emerging.

Power Distance Across Other Regions

- North America: The United States and Canada display relatively low power distance, fostering a culture of open communication and meritocracy (Hofstede Insights, 2021). However, hierarchical structures are still present in corporate environments, especially in traditional industries like finance and law, where seniority and rank continue to shape decision-making.

- Asia: Countries such as China and Japan exhibit high power distance due to Confucian values that emphasise respect for hierarchy and seniority (Farh, Hackett, & Liang, 2007). However, Japan incorporates consensus-driven decision-making, demonstrating a blend of high and low power distance characteristics (Nakane, 1970). In South Korea, leadership structures remain hierarchical, but younger generations are increasingly advocating for more participative approaches.

- Latin America: Countries like Mexico and Brazil have strong hierarchical traditions where leaders are expected to exercise authority and provide clear guidance (Davila & Elvira, 2012). The concept of paternalistic leadership is prevalent, where leaders take a protective role over subordinates. However, generational shifts and global business influences are prompting changes toward more open management styles in multinational companies.

- Africa and the Middle East: Many nations in these regions have historically high power distance due to tribal traditions and colonial legacies, where leaders command respect and decision-making is centralised (Jackson, 2011). However, South Africa, with its diverse cultural influences, shows a mix of leadership styles, balancing hierarchical structures with democratic elements influenced by post-apartheid reforms (House et al., 2004). In Gulf countries, such as Saudi Arabia and the UAE, leadership is often based on familial or tribal connections, reinforcing strong hierarchical structures, but globalisation is gradually introducing elements of participative leadership in international firms.

Effective Communication

Navigating workplace hierarchy across cultures requires more than just awareness—it demands a deliberate and adaptable approach. In environments where hierarchy is deeply embedded, leadership interactions follow a clear structure. Communication typically flows through established channels, reinforcing authority and maintaining order. For example, in high power distance cultures like China, direct communication across hierarchical levels is uncommon and can even be perceived as disrespectful. Leaders maintain an aura of formality and distance, often symbolised by their office space, attire, and the way they communicate. Authority is intertwined with age, experience, and rank, and subordinates show deference by adhering to established protocols (Meyer, 2014). In such settings, bypassing hierarchical levels can be seen as a challenge to leadership, making it crucial to obtain explicit permission before doing so. Even requesting a meeting with a junior team member may first require approval from their direct supervisor. Similarly, when addressing senior leadership, using formal titles and maintaining a respectful tone is often expected unless a more relaxed approach has been explicitly encouraged.

In contrast, leadership in egalitarian cultures follows a different rhythm—one that prioritises accessibility, direct dialogue, and an informal approach to hierarchy. Open-door policies, first-name basis interactions, and direct access to senior leaders foster a culture of inclusivity. In countries like Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, and Australia,leaders are expected to engage in casual conversations with employees at all levels, and rank plays a less rigid role in daily operations. The same trend can be observed in the United States and the United Kingdom, though regional variations exist (Meyer, 2014).

One of the key challenges in hierarchical cultures is the reluctance of subordinates to provide feedback. The belief that authority figures are always right can inhibit open dialogue, as employees may fear offering the “wrong” response. To overcome this, managers can adopt strategies that encourage communication while maintaining respect for their leadership role. One effective approach is to create opportunities for team members to brainstorm without the leader present, allowing employees to contribute ideas freely. Additionally, providing clear instructions before meetings about the leader’s expectations for input can make employees feel more comfortable sharing their thoughts. Leaders can also facilitate discussions by actively inviting team members to share their perspectives rather than waiting for them to speak up spontaneously. These methods help balance authority with collaboration, ensuring that employees feel valued while respecting cultural expectations around hierarchy (Meyer, 2014).

Team Management

Leading in egalitarian cultures requires a careful balance between autonomy and guidance. Leaders must avoid micromanagement while ensuring that teams remain aligned with organisational goals. One effective approach is management by objectives (MBO), in which leaders and employees collaboratively define clear, measurable goals. Rather than imposing directives, this method fosters a shared commitment to outcomes, granting employees ownership of their work while maintaining strategic oversight.

However, autonomy does not equate to the absence of leadership. Regular check-ins, such as monthly reviews, provide opportunities to assess progress, offer support, and recalibrate expectations as needed. The key is adaptability: some employees thrive with minimal intervention, while others benefit from additional guidance. By adjusting their level of involvement based on individual and team needs, leaders can foster both accountability and innovation. This approach creates an environment where employees feel empowered to take initiative while remaining aligned with broader objectives (Meyer, 2014).

Beyond MBO, leaders can reinforce ownership and accountability by promoting self-management. Granting employees the flexibility to make decisions and take charge of their projects not only boosts creativity but also deepens their commitment to achieving team objectives. Encouraging team members to assume leadership roles in specific initiatives or take on new responsibilities nurtures a sense of personal responsibility and empowerment.

Group decision-making practices, such as brainstorming sessions or consensus-building discussions, further support an egalitarian workplace by ensuring that all voices are heard and valued. Open feedback—both formal and informal—helps leaders stay attuned to team dynamics, making it easier to address concerns and identify areas for improvement. Additionally, fostering a psychologically safe environment for constructive conflict allows team members to challenge ideas and express differing viewpoints without fear of negative consequences.

Finally, symbolic actions reinforce an egalitarian leadership style. Simple gestures, such as aligning with team norms on dress code (e.g., avoiding formal attire if the team dresses casually) or using first names instead of titles, help break down hierarchical barriers. Rotating leadership roles during meetings promotes shared responsibility, signalling that leadership is accessible and collaborative. These small but meaningful actions contribute to a workplace culture that values openness, equality, and collective success (Meyer, 2014).

References

Earley, P. C., & Mosakowski, E. (2004). Cultural intelligence. Harvard Business Review, 82(10), 139–146.

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture and organizations. International Studies of Management & Organization, 15(1), 15–41. https://doi.org/10.1080/00208825.1980.11656300

Hofstede, G. (1980). Culture’s consequences: International differences in work-related values. Sage Publications.

Hofstede, G. (2001). Culture’s consequences: Comparing values, behaviors, institutions, and organizations across nations. Sage Publications.

House, R. J., Hanges, P. J., Javidan, M., Dorfman, P. W., & Gupta, V. (2004). Culture, leadership, and organizations: The GLOBE study of 62 societies. Sage Publications.

Jackson, T. (2020). The legacy of Geert Hofstede. International Journal of Cross-Cultural Management, 20(1), 3–17. https://doi.org/10.1177/1470595820915088

Meyer, E. (2014). The culture map: Breaking through the invisible boundaries of global business. PublicAffairs.

Triandis, H. C. (1995). Individualism & collectivism. Westview Press.

Trompenaars, F., & Hampden-Turner, C. (1998). Riding the waves of culture: Understanding diversity in global business. McGraw-Hill.

Leave a comment